I am working harder, longer than I did when at school. Families have different needs, different schedules and their new lifestyles are disorganized right now. I find myself struggling to balance between work time, me time, family time. -Workforce Survey Participant

The New York Early Childhood Professional Development Institute in partnership with the Bank Street College of Education recently completed a survey to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on New York’s early childhood workforce. The survey included early childhood program leaders, teachers, and family child care providers. Over 3000 individuals who are members of the state’s Aspire Registry responded. The survey sought to provide a descriptive snapshot of the workforce during the pandemic in order to stimulate dialogue to help as the field navigates this crisis.

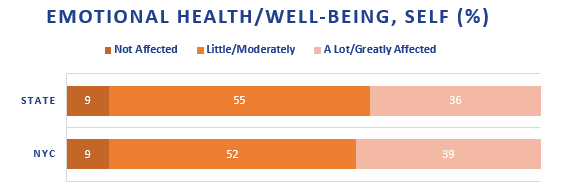

This year has brought a series of crises for each of us and all of us to navigate, to cope with and persevere through. Agencies and mental health practitioners have reported increases in emotional distress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Just 9% of the Workforce Survey participants indicated that their emotional health had not been affected; 38% reported being impacted “a lot” or “extremely,” the highest proportion among any of the stressors in the survey. For most participants, the emotional stress of the pandemic is more significant than the health and financial stress. Educators’ need for mental health supports exceed other areas of support requested.

The report states: With regard to ECE, the collective trauma that our community has experienced must be considered in light of developmental science that emphasizes the key role of caring, consistent adults to support children’s well-being. This, of course, means that parents and family members as well as early childhood educators help young children thrive. The data on educators’ mental health and well-being merit attention, particularly in light of emerging evidence that teachers’ stress (both personal and work-related) may be associated with children’s anger, aggression, anxiety, social withdrawal, and overall social competence.

Supporting young children’s learning involves being emotionally present so that you can connect to their ideas, efforts, strengths and interests. In light of the many structural inequities that the pandemic has magnified, this work has taken on a deeper and more critical role. Educators wear multiple hats to connect with their students–advocate, coach, care provider, mental health aid and counselor. The move to remote learning has amplified the necessity of these roles at the same time as making them so difficult to fulfill –often at the expense of educators’ well-being. For Black and women of color, our experiences are shaped at the intersection of class, race, and gender. We must examine and unpack our experiences in the contexts of such systems and find ways to survive, thrive and care for ourselves.

As expressed in the quote above, managing the demands of remote learning and balancing them with other responsibilities for their own families and their own health and mental well-being has been distressing for educators. Many well-intentioned guides and resources have focused on sharing time-management strategies to help us balance the responsibilities of work and home life. However, the crises that we are experiencing are multifaceted and the strategies needed to navigate them should go beyond planning and productivity concerns.

Below are some guidelines for leaders and educators that can help navigate these challenging times by focusing on self-care and setting healthy boundaries:

Self-Care

Give teachers breaks during the scheduled break time for mental health reasons, weekends are not enough of days off for teachers to recover and work on their own mental health. Teachers are working 3x harder with remote teaching regardless of their program or school and the rate of burnout will be much higher once this is all over. -Workforce Survey Participant

What does self-care look like? And what does this look like for Black and women of color? The mainstream ideal of self-care is highly commercialized and predicated on assumptions around health and wellness that are not accessible by all. Furthermore, it perpetuates the idea that there is a “correct” way to self-care.

Audre Lorde, a feminist and activitist, wrote “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare”. For our communities, to survive and persevere is to thrive and that in and of itself is a political and rebellious act. It is resistance and resilience in the face of adversity and injustice. Our communities have historically dealt with structural inequities related to poverty, housing, healthcare, unfair wages and so on. It begs the question, what does self-care look like for us? In light of these contexts, how can our communities create and prioritize self-care?

This month the Leadership Initiative hosted Elena Aguilar to share her work on cultivating emotional resilience in times of crisis and change. Her work outlined the following ideas:

- Naming Emotions and understanding their intensity

- Identifying and describing our emotions can be difficult as they are complex and range in intensity. In our current context, we find ourselves feeling fatigued, overwhelmed, stressed, perhaps even numb. As Aguilar writes, these are not specific emotions, they are a mixture of different emotions and mediated by the external environment. Emotions will vary in how we experience them, feel them and how they manifest internally as well as externally. Noting and putting a name to our emotions is a critical step in making decisions about how we will deal with these emotions. Learning to recognize how intense emotions manifest in our body. e.g. hand shaking, tensing of shoulders, jaw, etc. can help us shift our response. Breathing exercises help curve the physical and mental toll of these emotions.

- Understanding Burnout

- Burnout is defined as the physical and mental toll caused by prolonged stress and can be “characterized by apathy, fatigue, frustration, anger, depression and dissatisfaction” (Aguilar, p. 55). Managing your energy can help you to be aware of when you may be approaching burnout. Taking account of our emotional and physical state, how might we describe what we are feeling?

Creating and Maintaining Healthy Boundaries

Compartmentalizing work time vs. me time vs. family time. At first I told staff that my hours of work would be 8-3:30pm then I had to push it to 8-6 pm but now I’m doing work (helping teachers) almost (until) 9-10 pm – Workforce Survey Participant

You have the freedom to set boundaries. The changing demands of remote learning have contributed to blurring the lines between home, personal and work life. We’ve heard stories of educators going above and beyond to support the needs of their students and their families during this pandemic, such as reading a bedtime story to a child who had difficulty falling asleep. This story is heartwarming and a testament to wonderful educators and their dedication to their students. However, as nurturing and generous as we aim to be, we must also wonder whether we are extending the same kindness to ourselves and our well-being.

Some thoughts to reflect on:

- Do a body scan, check in with your emotions. Jot down your thoughts and put a name to what you’re feeling. This can help determine what we are able to take on this day and prioritize our most pressing needs.

- Create boundaries around work hours. You can can not care for others without taking the time to care for yourself. As a teaching team, how can you create dedicated time to respond to the needs of children and families? Educators have expressed that setting brief, weekly check-in calls and aiming to create this consistency can alleviate stress and protect our time.

- Lean in to community and support systems. Workforce Survey participants indicated that reliance on families and friends was their greatest mental health support. As leaders, how can you help build community within your programs? The Leadership Initiative can connect you to a strengths-based coach or a weekly networking meeting. Such efforts are even more necessary in these difficult times.

Read the full report: New York Early Care and Education Survey: Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on New York Early Childhood System

Bibliography

Aguilar, E. (2018). Onward: Cultivating Emotional Resilience in Educators (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Lorde, Audre. (1988). A burst of light : essays. Ithaca, N.Y. :Firebrand Books

Share in the chat: What policies and practices can be shifted to alleviate your work-related stress?

Ivonne Monje and Tatiana Bacigalupe are Screening and Assessment Specialists at the Institute.