The events of the past 18 months have given rise to a massive global civil rights movement that has invited deep reflection and calls to action for all of us. As part of this movement, the field of Early Care and Education has begun to question its foundational structures, and there are a range of viewpoints among thoughtful people about the changes that are needed. State and city agencies have paid increasing attention to addressing racial inequity in child welfare, including strengthening protective factors. At the Institute, the Gender, Sexuality and the Family team leads us to joyfully imagine a kind and just future for our society. Milo Giovanniello, a member of that team, wrote this post about their journey as an abolitionist educator.

For me, being an educator is inexplicably tied to my work as an abolitionist. I want my work with young people to help them understand that their lives and thoughts matter, that I value their self-determination. And I want to spend my life working toward building a world without police and prisons, a world where jails cannot even be imagined. When I think about abolition, I think of Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s reminder that abolition is not just about the absence of prisons but also the presence of systems that actually care for people and meet their needs.[1] Prison and police abolition demand from us new ways of caring for one another and of reckoning with harm without seeking to dispose of one another.

I know we are a long long way from living in that world, that our society is so reliant on and accustomed to carceral logics that it’s hard for us to see how deeply they’re woven into our everyday lives. A big part of how I started unlearning my own beliefs about punishment and vengeance was as a preschool teacher. Previously, I had worked in a charter school where kids were often suspended for small deviations from the behavior expected of them, where I felt like the best I could do was to try to mediate the harm caused by anti-Black racism from teachers and principals, and where I often failed.

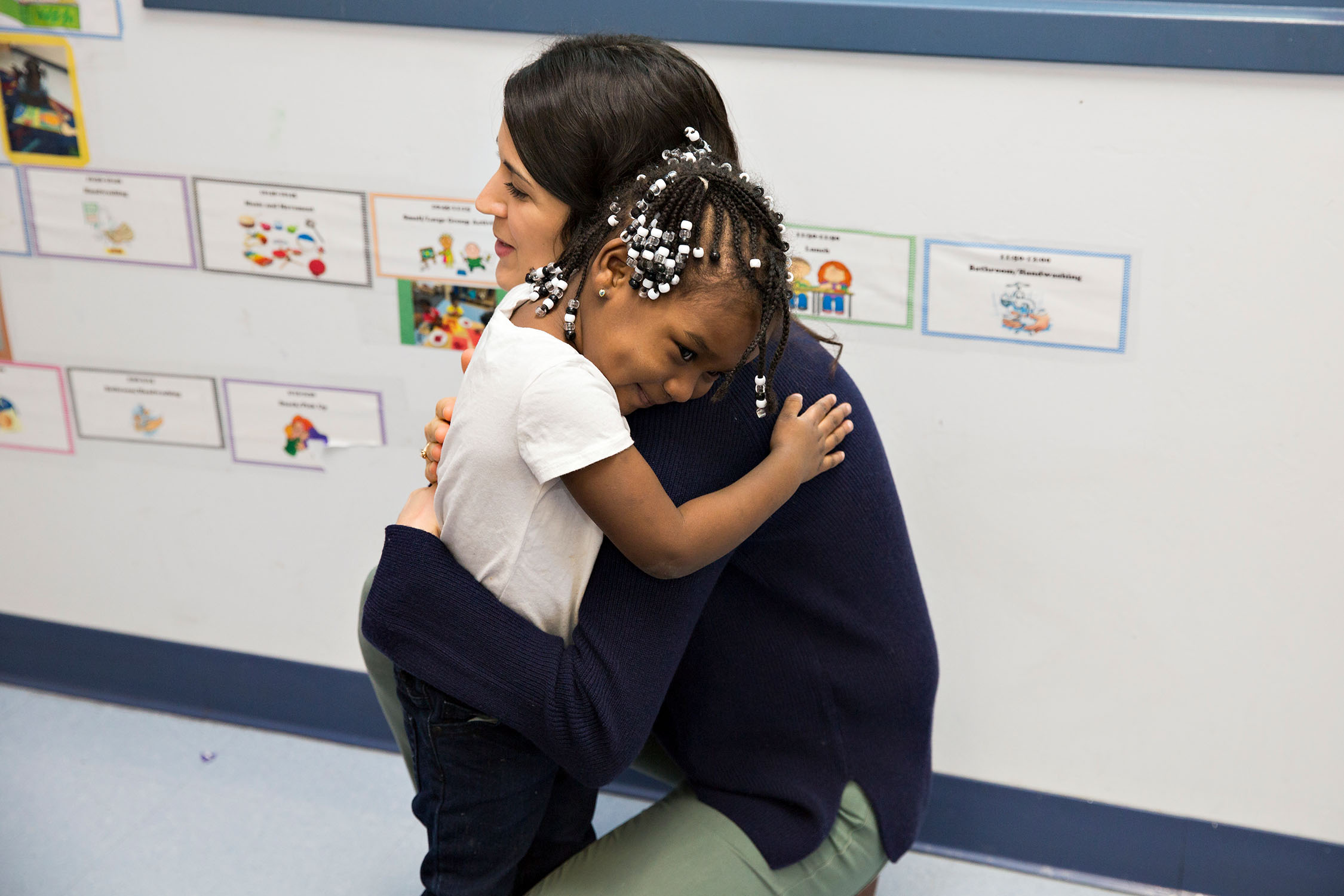

In my new job as a preschool teacher, I spent a lot of time asking kids questions. Sometimes they pushed or hit or made each other cry, and I learned how to describe what was happening: “I see that Lucas is crying. It looks like he didn’t like that. Can you ask him how to make it better?”

I had been a part of racial justice organizing before becoming a preschool teacher. I had learned from friends and neighbors and comrades who taught me that we did not need police and prisons, that these institutions were made to harm Black and brown people, that I could not claim to care about racial justice if I was not also working to end the prison industrial complex. But I had never spent so much time thinking about what transforming harm could look like if disposing of the harm doer was never an option. It was 3 and 4 and 5 year olds who taught me that there are infinite ways of repairing harm, that only the person harmed can let us know how to “make it better.” I learned that teaching kids to ask one another before hugging was about teaching them that their bodies were theirs alone and that another child’s ‘no,’ or uncertainty, or confusion mattered, and was always reason to pause.

At the same time, I took several mandatory reporting trainings which aimed to persuade me that if I ‘suspected’ any kind of abuse or neglect it was my role and legal obligation to alert CPS. I knew I could never live with myself if I made the call that meant a child lost their caregiver. I had read too many stories of Black and brown mothers struggling for years to gain back parental rights, of how much trauma the foster system and forced separation from their caregivers inflicted on kids.

As Movement for Family Power teaches us, the foster system overwhelmingly targets Black people. In 2008, Black children were 27% of the total population but comprised nearly 57% of children in the NY foster care system. In 2016, Black families were 6.3 times more likely than white families to be investigated by child welfare authorities.[2] Over one third of American children and over half of Black children have been the subject of a child abuse or child neglect investigation.

Dorothy Roberts, a scholar of race, gender and the law, details the story of a mother who called 911 after an argument with her boyfriend, and then received a visit from Child Protective Services. Because she told the caseworker that she smoked marijuana from time to time, the caseworker initiated a child neglect proceeding and the court implemented a “family service plan” which demanded that the mother attend “parenting classes; anger management classes; parenting classes for children with special needs; participation in a drug treatment program; submission to drug testing; submission to unannounced visits from CPS, including full access to the apartment for inspection; and participation in all family court conferences and hearings, regardless of her work schedule.” When the mother was unable to comply with these demands, her children were taken away from her and placed in foster care.[3]

As Roberts explains, “The government claims to protect children from monstrous parents when, in fact, it destroys families and inflicts extreme trauma and other harms on the children it claims to help.[4]”

I know that taking children away from their parents almost always causes more harm, and I was not about to use my power as a teacher, power I was coming to understand as fragile and tremendous, to make a call that could turn anyone over to the hands of the state. As preschool teachers this is the tension we must grapple with. What does it mean to see the harm that the foster system and CPS causes and to be legally obligated to make these calls? How can we live with ourselves if we make a call that ends up tearing apart a family?

Holding this tension means that I had to figure out how to intervene in the harm without inflicting further harm or trauma. Intervening might look like talking to the family members we know, sharing our concerns, finding out if there are trusted neighbors or other caregivers who can provide support, or if the family actually needs other resources (food, therapy, housing, childcare) that we can help them access.

There are not clear answers, but I have been inspired by the work of Generation Five and Movement for Family Power.

Movement for Family Power’s policy recommendations to protect children from abuse offer us a concrete way of understanding abolition as the presence of systems that actually care for people, as well as the absence of systems that cause harm, like CPS. They call for increased funding to social safety nets like cash assistance, health care, housing, and childcare. In Erin Miles Cloud’s words: “to end the systematic policing and punishment of families, we must engage in the praxis of transformative justice and dismantle the foster system.[5]”

In their powerful reflection on their own experiences of childhood sexual abuse, Ignacio G Rivera and Aredvi Azad lay out the steps they believe are necessary to prevent childhood sexual abuse and care for survivors while not allowing the police and CPS to intervene and cause further harm.[6] They call for prevention through education, family and community response (when harm happens), free immediate care, free long-term support, and breaking the cycle of harm (via transformative justice). As family and community members we might be a part of any of these necessary interventions, but as teachers we are especially well-positioned to support preventative educators by teaching the young people we care for about consent, self-determination, and bodily autonomy.

In my own work with the NY Early Childhood Professional Development Institute, I feel so grateful to get to have conversations with early childhood educators about how we can more fully incorporate consent education into our work with young people. Teaching consent practices is one way of supporting the cultural shift that abolition will require. We hope to support young people to feel empowered, to notice what feels good to them and what doesn’t, to notice when someone else isn’t feeling good, to have the tools they need to negotiate interpersonal conflicts and harm.

Like many others, my teachers and family members did not have the tools they needed to give me these lessons when I was young, and I have had to work to learn these for myself as an adult. I know that young people need and deserve to learn about consent, self-determination, and bodily autonomy, and that by offering this learning, we are working to build a future where less harm happens, where Black lives are actually valued all the time, where survivors of the harm caused by policing, prisons, and CPS are believed, and survivor’s needs are centered.

Milo Giovanniello is on the training team for Gender, Sexuality and Families in Early Childhood at the New York Early Childhood Professional Development Institute.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/17/magazine/prison-abolition-ruth-wilson-gilmore.html

[2] Office of Children and Family Services, “Black Disparity Rate: Unique Children in SCR Reports CY,” 2016; Wildeman, Edwards and Sara Wakefield. 2019. “The Cumulative Prevalence of Termination of Parental Rights for U.S. Children, 2000–2016,” https://doi.org/10.1177

[3] Ibid

[4]http://sfonline.barnard.edu/unraveling-criminalizing-webs-building-police-free-futures/how-the-child-welfare-system-polices-black-mothers/

[5]http://sfonline.barnard.edu/unraveling-criminalizing-webs-building-police-free-futures/toward-the-abolition-of-the-foster-system/#footnote_5_4262

[6] https://racebaitr.com/2020/08/26/police-cant-save-children-from-sexual-abuse-but-we-must/

What a powerful re-thinking of how children can SHOW us how to keep our communities safe and repair harm! I’m so grateful you and this team for continuing to push the boundaries of our imaginations so we can create a more just world. Milo, thank you for this!

Thank you, Milo, for this rich reflection and statement of purpose in your career. As a center director for many years, I found it incredibly difficult to find any nuanced interpretation of mandatory reporting when the teachers working with me felt compelled to follow the letter of the law because of the training they’d received. Though Dorothy Roberts’ story details a response from authorities far more complex and harmful than what I have experienced from agencies that are under-staffed and over-worked, it is still our worst nightmare. There needs to be more discussion about how to protect our most vulnerable – children, which is our foremost ethical requirement, and at the same time not do more harm!