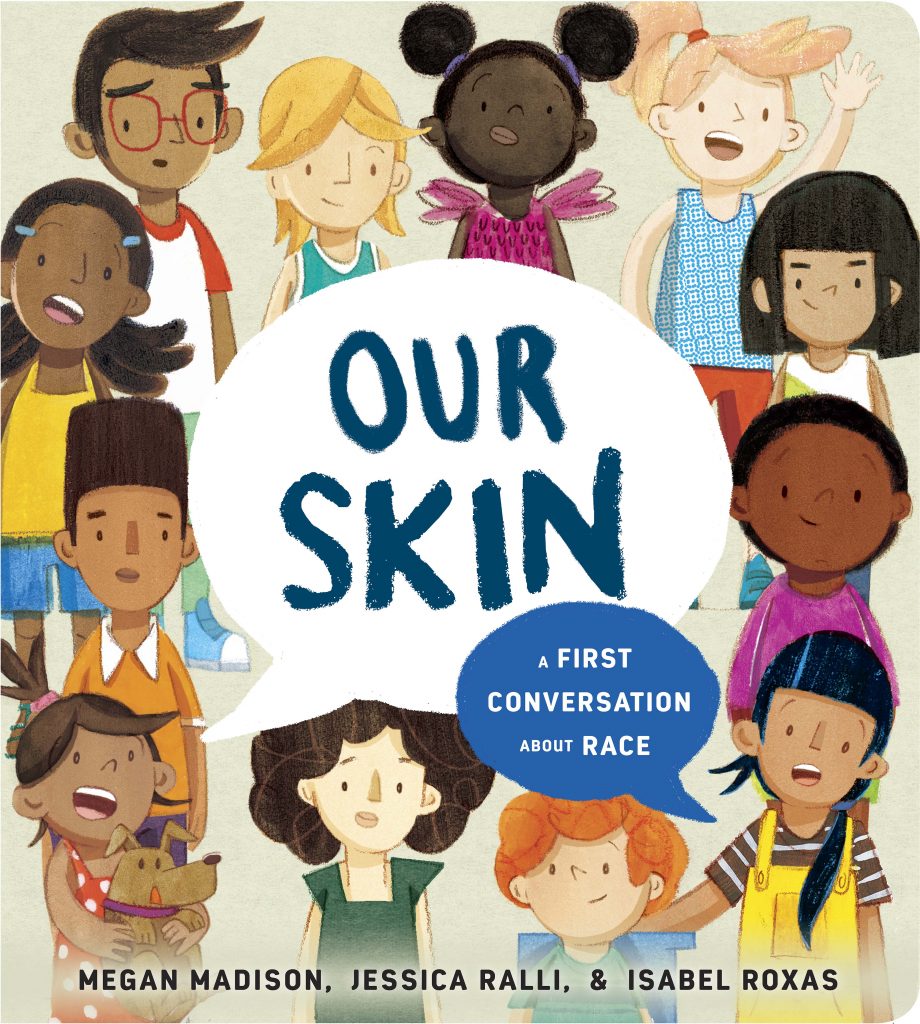

Megan Madison, an innovator at the intersection of social justice and early childhood as well as the leader of the Gender, Sexuality and the Family team at the Institute and Jessica Ralli, the Coordinator of Early Literacy Programs at Brooklyn Public Library, have recently published the Our Skin: A First Conversation About Race. This book is the first in a new series designed to support adults in having open and expansive conversations with children about race, gender and justice.

The first book, Our Skin: A First Conversation about Race came out March 16th. And then the second book in the series, Being You: A First Conversation about Gender comes out July 13th. The other two books, a First Conversation about Consent and A First Conversation about Bodies (and body liberation and body positivity) come out in 2022.

Helen: What would you like to share about yourselves and how you came to this work?

Jessica: Let’s see, well I’m Jessica Ralli and the pronouns I feel good to me are she and her and I am a white cisgender woman. I’m the mom of two young white children and when I’m not doing that, I’m the coordinator of early literacy programs at Brooklyn Public Library. I love libraries! I’m also a former early childhood preschool special education teacher. I do really miss being in the classroom with kids, but I’m glad my work at the library lets me do that on a regular basis – at least it did before the pandemic, and I’m looking forward to working with kids in person again.

In terms of what brought me to this work, there’s really so much that I could talk about, but most recently it’s my work at the library and my experience as a parent. When my kids were about two and four, I was really determined to have intentional conversations with them around these topics, especially around race and gender.

Working in a library, I always turn to books first and so I really dug into what’s out there about race, racism, gender and feminism. First of all, there aren’t that many of them, and the ones that I found are either written for older children and a lot of the books for younger children use complex terminology without really explaining it -metaphors, and language that people may thinks is cute for young children, but it doesn’t really express ideas to them in the way that they learn and and understand. There are lots of rhyming books about complex topics for young children, and then a lot of the books also stop at celebrating diversity, and I think that’s great, but that’s already as far as a lot of people will go.

So in any case, I think the books that are out there are wonderful tools, but really, only if you know how to use them to have deeper conversations about systems of oppression like patriarchy and racism. So, I thought it would be great if there was a series of books that actually supported these kinds of conversations. I thought “somebody should write those books and they should be board books so that they really get into the hands of young children!” The rest is history.

Megan: My name is Megan Madison. I use she and her and hers pronouns and I have lots of identities, but some that feel relevant here are that I identify strongly, proudly, unapologetically as a Black person. I love being Black. I’m also queer. I’m also cisgender. I’m a woman. Those are some things that feel relevant.

I come to this work through my early childhood background. I have been working with young children, in lots of different roles, for a while. I’ve worked as an assistant in a Waldorf program and as a lead teacher in a Head Start program. I’ve worked as a nanny. I am an auntie and a godmother to some young children that I love. I don’t have any kids of my own yet.

Now I spend a lot of my time working as a teacher teacher, supporting educators who work directly with young children to think about how they might be brave and have explicit conversations about things like racism and patriarchy with young children and their families. And I came to this work because I was leading workshops for early childhood educators and Jessica brought me in to do some of those workshops at the Brooklyn Public Library. And we kind of built a relationship from there.

Helen: Do you want to talk a little bit about First Conversations as a series and just describe the books a little bit?

Jessica: I can give it a go. First Conversations is a series of board books. The age group that we wrote for is around two to six, but we’re hoping that people use these books with older kids too, and that grownups learn a lot from the books, so they’re really for everybody. They’re on different topics that grownups have a hard time introducing to young children, like race, gender, consent, and body positivity. Finding the right language to go beyond just celebrating diversity and delving into talking more about systems of oppression and what we can do to fight and disrupt those systems of oppression.

They are so beautifully illustrated! We wanted them to be illustrated in a way that children feel seen and can really see themselves represented. We also wanted them to see scenarios that they might find familiar, so a lot of the settings are in home and school and park environments where children spend a lot of their time.

In the backmatter we provide resources for grown ups who want to deepen the conversations they may have after reading the books with their kids or in their classrooms.

Helen: Why are these first conversations so important?

Megan: That is a good question. I’m still thinking about the last question, and maybe it’s a good bridge. I’m thinking about how each of the books is written. Underneath each of them is the framework of anti-bias education. So thinking for every reader we want the book to provide language and imagery that supports them in developing a proud sense of self, of knowing who they are in relation to these concepts of race and gender and to feel good about who they are. And then there’s also language and images that support kids in understanding that, it turns out there’s a lot of diversity among us humans, and not everybody is the same as who they are. And then there’s lots of words and opportunities to explore that diversity, and get comfortable with it, and talk about it instead of shushing it or pretending it doesn’t exist. And then from there there’s language and images in each of the books that talks about the justice piece, to help kids have words to explain the really big unfair things that exist in the world around them. And then from there there’s space to talk about activism and the different strategies that we have to do something about the really unfair things we see in the world related to race and gender. So I feel like that’s an important piece of the books.

Why is it so important to start those conversations really early with young children? Because we know that it’s a critical point in life to develop that sense of self. They’re becoming – especially I’m thinking about toddlers – like citizens of the world in some ways for the first time. Walking down the sidewalk in the stroller and looking out and seeing like, oh my gosh, there’s all these people in the world that aren’t just my family! What’s going on here?

And they have lots of questions and observations, and while they’re doing that observing they’re also seeing really unfair things. And developing hypotheses about why these patterns exist in our world. And a lot of us grown ups didn’t have grown ups in our lives when we were that young who were practiced and comfortable having those conversations with us about what we were noticing. So it can be hard for us to figure out how to do a thing that no one modeled for us. So I also think these books are a tool to support us.

Many of us know, oh, we’re supposed to be talking about race. We’re supposed to be talking about gender with young children – but there is this big question of: ‘how?’ What am I supposed to say? What am I not supposed to say? And so these books are somehow like a scaffold. They’re support to help us as grownups get a little bit more comfortable, a little bit more brave in having these conversations with young children when they start to make these noticings, not, you know, well after. We don’t want to wait ‘til they end up in college and they’re in their first African American studies course and they’re like: What?! Racism is systemic?! Why didn’t anybody tell me?! Like we don’t have to wait ‘til then. We can start now. Really.

Helen: Thank you so much. In all your professional development and family engagement experience, what do you notice does hardest for adults about having these first conversations with children?

Jessica: I think finding the right words to explain things to young children in general is really hard. You know a conversation with a toddler can go off the rails very quickly, and that’s a lot more scary when you’re talking about something as complex, sensitive, or as personal as race and racism, or gender. I also think people are afraid of saying the wrong thing, so it’s about that need to find the right words and also being really afraid of finding the wrong words. I think for white people that has a lot to do with white supremacy culture and the need to be perfect all the time. In this case finding the perfect thing to say about race and racism and not wanting to be wrong. As Megan said earlier, the most common question that I noticed after the workshops at the library was, was “How?”. How do we do it? You know, you’re telling us why it’s important, but how do I do it with my child? What are the words that I use?

Even though there is no script it does help to have a model and some idea of the language you might use. These books are meant to scaffold and build on what young children are already learning, what they’re already seeing and what they’re already asking questions about. I think giving people the answer to “how” is more about giving them a doorway and model for how to do that.

Megan: Uh huh. I would add; I think of two main challenges. I think one challenge is that most of us are not very fluent or not very literate in the core concepts around race and gender. And that’s not our fault, but many of us did not receive adequate education around it, and so it actually takes a lot of knowledge and fluency and understanding to be able to take these concepts, and boil them down, and communicate them clearly in ways that young children can understand. So I think one big challenge is that a lot of us have a lot to learn. And we’re learning alongside young children.

And I think part of that is also that there’s a mismatch between what we think we know and what we actually know. Sometimes I think of it like the beautiful developmental stage of like 3 year olds. You know where they’re like: “I’m a big kid now!”And they’re like, “I got it. I figured it out. I’m bold. I’m brave.” Like, “I don’t want to ride in the cart at the grocery store. I’m going to walk!” And then you get to aisle 4, and they’re like: “Please put me in the cart! I’m tired!.” And I feel like,as a country,that’s where we’re at developmentally around race. There’s a lot of confidence,which is beautiful, but actually and developmentally, like we breakdown around aisle four. We just have a lot of growing to do and we get to do it with each other.

And I also think that developmentally appropriate practice is really hard to do. Like I was just reading through the more updated revision and the core ideas are that there are some things that are unique to any individual kid, and there are some things that are more universal about child development that you should know, and there are some things about the specific historical, social, structural context that we need to take into consideration.

And, as early childhood educators, you have to take all three of those things and hold them in your mind at the same time! The context, what we know about child development, and all the things you know about that individual child and family. And use all of that information at the same time to make an informed decision in any given moment. And that is also true about talking about race and gender, and it’s a lot to hold!It really is a challenge!

I think we can do it. I really do think early childhood educators are some of the smartest human beings on the planet, and it is a really big ask to stay like really listening, attuned to this particular child. Who they are, what they’re interested in, how tired they are today. Did they have snack?

You know, and also think about, what do we know about how race and gender shape the developmental trajectories, on average, for many kids in this country? All the research on child development.

And also think about, like, where and when am I having this conversation? Is this the first week of school, or is this you know, six months in? Is this during Black History Month? Do I serve, you know, mostly indigenous kids in a rural Head Start program in Oklahoma? Or do I serve middle class white kids in a public kindergarten in Miami? Or a multiracial group of infants and toddlers in a progressive private child care program in Brooklyn? Like the context really matters for making the particular decisions about what conversation you’re going to have and how you’re going to have it.

So I think the challenge is just that it’s actually really hard. We’re asking early childhood educators and caregivers to do a really, really complicated and challenging thing. And I think these books will help.

Helen: Thank you. My next question is: How do these books support children’s sense of belonging, and what changes for children when they feel like they belong?

Jessica: I really, really love this question and it got me very emotional thinking about it. I think we tried really hard with the illustrations to represent lots of different kinds of people, families, skin colors, abilities and gender expressions. And it was really hard.

We talked about it a lot, because I think we always felt like we were missing someone.But part of the reason we tried so hard was that we wanted children to know that this book is for them, and that they belonged in the story. It’s their story and it’s for them.

I think belonging in a school environment for children means young children can learn. It opens their senses. It builds neural connections in their brain. It makes children feel connected to one another which builds empathy. And then at home, belonging is love! Belonging means you’re loved and feel seen and heard. I think this book is about building that connection of children feeling heard and listened to and being given language to express themselves. So that they can feel connected and loved and like they belong.

Megan: We hope. I’m thinking about what it feels like for me when I read our books. And our illustrators on both of the books are really talented. When I read through the books, and I look at the illustrations, there’s no one character that looks exactly like me, but there are moments where I do see myself in the book. For example, there’s a page in the book on race where there’s a Black girl who has a giant ice cream cone, like six different flavors of ice cream stacked on top of one another, and I am a Black girl who loves ice cream that much. So there’s something about being able to open a page of a book and see something like that. Not just my skin color, I actually think that me and that character have different skin colors, but to be able to see another Black girl who loves ice cream as much as I love ice cream, it opens up something in my heart to be able to feel like, oh, this book was written for someone like me. This book was written with someone like me in mind. It sends a subliminal message that I am right in the world, exactly as I am. That I don’t need to translate myself in order to be legible, in order to be loved. And when I’m not doing all of that extra work of translating myself, I can actually learn a lot better. I can make more sense of the content of the book itself. The text.

My hope is that the book does this for so many children and families that don’t usually feel a sense of belonging in classrooms and children’s literature.

Helen: What was new or surprising to you about writing the children’s books?

Megan: Everything – how books are made is so interesting! The whole process of writing, and then rewriting, and rewriting…and rewriting, and then it going to copy editing, and getting more changes to the language. The process of being matched with an illustrator who we didn’t meet until well into the process. The fact that there’s a whole marketing team that is doing all this work to make this book come alive and get it into the hands of people.

Jessica: Oh yeah, every aspect and it continues to be a mystery every single day. All of that. There’s still so much we don’t know. I think what surprised me the most is what a team effort writing books is like.

I kind of had this image of like a writer sitting alone at a table and like you know, just writing the book and then it gets published. But first of all I am blessed to have Megan as a co-author and I love the process of writing together. Because I think it really allowed both of us to bring our strengths to the work and that felt really, really great. I think the editorial process was really, really surprising for me too because editors have a big influence on the way books are written, and in our case that was a wonderful thing because we have a great editor, but it made me think about all the other books out there and the stories that maybe aren’t getting through because there’s just a lot of editing. Our editor really helped us to distill the main messages the ideas of the books and kept reminding us who the audience was, which was really helpful.

I think just in terms of publishing industry, I feel like we both noticed that there’s a need for many more voices at the table and I think that’s something that our team at Penguin, which is a very small team in a very big publishing house, are very aware of. Publishing is still incredibly white, and while I think doors are opening for sure, it’s not enough, and it’s not fast enough. It feels like something that if Megan and I get to continue writing these books, that we can figure out a way to keep pushing from inside and outside of the industry to keep bringing more voices to our books, and maybe even influencing other projects.

Helen: Thank you. Who were the other authors and educators that inspired you to do this work, or that you know you looked to or thought about when you were writing the books?

Megan: Well, anything I know about race and young children I learned from Ijumaa Jordan. Ijumaa deserves an incredible shout out. Another colleague, Kate Engle, was incredibly supportive. In particular, Kate has a lot of experience being a white person, but also being a white educator who’s taught white kids and so she helped us in thinking about (not centering), but thinking thoughtfully about what are the developmental needs of white kids who are learning about race and racism.

Also Laleña Garcia, who has just been such a trailblazer and a person who’s in the classroom right now, having these conversations with young children. And has been so generous in sharing her wisdom and insights about how she translates a lot of these big concepts like systemic racism into kid friendly language.

Who else?

Jessica: Well, Megan was my greatest inspiration. The workshops that Megan did at the library were a huge part of why these books are even happening. I remember the first workshop that I went to where Megan was facilitating and I just wanted to take everything that she said and keep it and listen to it over and over and over and over again.

Megan -has a way of illuminating ideas that I had felt, but had not yet really been able to articulate. I also saw the impact that Megan has on people in the room –being able to open them up and allow them to be vulnerable. And she is so supportive as people move through new ideas and feelings. I had never seen anything like that, and I wanted to put that feeling in these books somehow! All of these individual experiences are going to start happening once these books get out into the world, and I’m hoping it feels a little bit like being in a room with Megan.

Jessica: I was also going to say Laleña, whom I had asked Laleña to be a speaker at one of our events last year. Reading all of her incredible resources and her approach to talking about Black Lives Matter to young children has helped me so much as a parent.

In terms of authors, there are so many that swirl around my head. or this book in particular, Katie Kissinger’s book about melanin, All the Colors We Are, was a really big inspiration.

This was just such an impactful book to read with young children because they are so curious about skin color, and it explains things in such a clear way. Also Cory Silverberg. Cory Silverberg’s books were really influential, especially for our book about gender.

Megan: And also, you know always, Louise Derman-Sparks and Julie Olsen Edwards and Carol Brunson Day and their work around anti-bias education. And the whole team, the gender, sexuality and family training team at PDI. It’s been incredibly supportive to have that community of practice. And our friends at Gender Justice in Early Childhood in the Bay Area!

Helen: Historically, pandemics have forced people to break with the past and imagine another world. For the young families who might read these books well, world, would you imagine them growing into?

Jessica: This was another one that I thought about late last night and hoped it would come to me in a dream. But it didn’t. It came to me a little bit later towards the morning and I thought about 3 words: Listening, Believing and Liberating.

I would like for us to grow into really great listeners. To listen to each other’s questions and to listen to each other’s pain, and to really listen to children and what they’re thinking and feeling.

And then in terms of believing, I want us to grow into really great believers. Believing people who say that they’re being oppressed, that they’re being hurt. Believing people who say that they know who they are. Believing and trusting ourselves and, especially believing children. This plays out so much with young children in the classroom.–understanding somebody else’s perspective is also about believing them when they say they’re feeling and thinking something.

And then liberating. I want us to grow into liberators, and to understand that our liberation is connected. I want for people to see that it’s up to everybody to be free and to be liberated, not just certain people who don’t feel liberated. So those are my words.

Megan: I like this words approach – the words that are coming up for me are safe. I want kids and families to feel safe. I want them to feel loved. I want them to be healthy. I want them to be free. And I want community. I want us to recognize and be able to practice together what ways to keep each other safe and loved and healthy and free. Knowing that we actually can’t do it as individuals like we, we need each other.

And in order to do that, we need to communicate with each other. We need to be able to communicate with each other clearly about what we value and why, and what we need and what we feel. And exactly as you said, Jessica, we need to believe each other when we communicate that, and be able to listen to it, and take it seriously, and then collaborate to meet our needs collectively.

Helen: That’s lovely. Is there anything that you want to add?

Megan: Just thank you, for being such a supporter of this work. It really matters.

Helen: Thank you. I’m so excited about it. I really am. I feel so hopeful and it’s nice to feel hopeful.

Jessica: That’s been a big thing that Megan and I’ve talked about throughout this process is just how grateful we are to be working on something that makes us feel hopeful at this time. There’s just so much about this moment that I think has heightened our awareness of what needs to be in these books and made us feel very hopeful in the process, and that’s been really nice to have.

Megan: I think one other thing to say is that I hope that when these books actually are in the hands of teachers and caregivers and young children, that they tear them to shreds.I have no illusions that we did a perfect job. That wasn’t the goal. Our goal was to get brave and put something out there. I hope there are some things that we’ve put out that really work for people and that they can use. And I also hope that people say goodnight to the things in the books that don’t work for them, and share loudly what doesn’t work and what alternatives they suggest. Our whole goal with these conversations is to start a conversation (or to continue a conversation) and keep it moving. You won’t hurt our feelings with your questions and critiques. We want to hear them! We want this conversation, we want our collective thinking, to continue to move forward as a community.

Order copies here: First Conversations

I have just received a copy of your book, Being You. There are, of course, many wonderful things about it but what I appreciate most is your page with the presidents excluding the one who was/is a violent ruthless traitor.

Thank you.